if cause: คุณกำลังดูกระทู้

Table of Contents

The Four Causes

What are there four of?

-

Aristotle’s doctrine of the four causes is crucial, but easily misunderstood.

It is natural for us (post-Humeans) to think of (what Aristotle calls) “causes”

in terms of our latter-day notion of cause-and-effect. This is misleading

in several ways:-

Only one of Aristotle’s causes (the “efficient” cause) sounds even remotely

like a Humean cause. -

Humean causes are events, and so are their effects, but Aristotle

doesn’t limit his causes in that way. Typically, it is substances

that have causes. And that sounds odd.

-

Only one of Aristotle’s causes (the “efficient” cause) sounds even remotely

-

But to charge Aristotle with having only a dim understanding of causality

is to accuse him of missing a target he wasn’t even aiming at. We must keep

this in mind whenever we use the word “cause” in connection with Aristotle’s

doctrine. -

We will begin with the question, What is it that Aristotle says there are four of? The Greek word is

(plural ); sometimes it takes a feminine form, (plural

). And what is an ? Part of Aristotle’s point is

that there is no one answer to this question.An is just whatever one can cite in answer to a “why?” question.

And what we give in answering a “why?” question is an explanation. So an

is best thought of as an explanation than as a cause. -

Even so, that’s not enough. First, Aristotle thinks that you can ask what the aitia of this table are, and it’s

not clear what sense, if any, it makes to ask for an explanation of the table. Second, he

thinks that, in some sense, a carpenter is an aition of a table, and it’s not clear in

what sense, if any, a carpenter (or anything like a carpenter) could be an explanation of

anything.Here perhaps Ackrill’s “explanatory factor” is a more illuminating translation of

aition. That is, an aition is something that plays a role as an explanatory

factor in the explanation of something. But, as we’ll see, there are many kinds of explanations.

Where to find the doctrine in Aristotle’s texts

-

In RAGP: . II.3; and (extensively) in . A.3

ff. See also . 639b12ff -

Additionally (not in RAGP): . II.11; . Δ.2;

335a28-336a12.

The traditional picture

The picture is Aristotle’s, but the names of the causes are not. Quotations from Physics II.3, 194b24 ff:

-

Material cause:

“that out of which a thing comes-to-be and which persists is said to be a cause, for example, the bronze is a cause of a statue, the silver is a cause of a bowl, and the genera of these [is also a cause].”

-

Formal cause:

“the form or paradigm, and this is the formula of the essence … and the parts that are in the formula.”

-

Efficient cause:

“the primary starting point from which change or rest originates; for example, someone who has given advice is a cause, the father [is a cause] of a child, and in general what does [is a cause] of what is done and what alters something [is a cause] of what is altered.” -

Final cause:

“[something may be called a cause] in the sense of an end (telos), namely, what something is for; for example, health [is a cause] of walking.”

This account makes it seem as if Aristotle is offering a catalog of causes, and is claiming that

each thing has four different kinds of cause. But what the account misses is the idea that there

is something ambiguous about the notion of aition.

The ambiguity of aition

Aristotle warns us of the ambiguity at 195a5: “causes are spoken of in many ways.” This is his usual formula for telling us that a term is being used ambiguously.

That is, when one says that

is the of , it isn’t clear what is meant until

one specifies what sense of is intended:

- is what is [made] out of.

- is what it is to be .

- is what produces .

- is what is for.

This makes it hard for us to get clear on what Aristotle was up to, since

neither “cause” nor “explanation” is ambiguous in the way Aristotle claims

is. There is no English translation of

that is ambiguous in the way (Aristotle claims) is. But if

we shift from the noun “cause” to the verb “makes” we may get somewhere.

The ambiguity of makes

Aristotle’s point may be put this way: if we ask “what makes something

so-and-so?” we can give four very different sorts of answer—each appropriate

to a different sense of “makes.” Consider the following sentences:

- The table is made of wood.

- Having four legs and a flat top makes this (count as) a table.

- A carpenter makes a table.

- Having a surface suitable for eating or writing makes this (work as) a table.

Aristotelian versions of (1) - (4):

1a. Wood is an of a table.

2a. Having four legs and a flat top is an of a table.

3a. A carpenter is an of a table.

4a. Having a surface suitable for eating or writing is an

of a table.

These sentences can be disambiguated by specifying the relevant sense of

in each case:

1b. Wood is what the table is made out of.

2b. Having four legs and a flat top is what it is to be a table.

3b. A carpenter is what produces a table.

4b. Eating on and writing on is what a table is for.

Static vs. Dynamic Causes

Matter and form are two of the four causes, or explanatory factors. They

are used to analyze the world statically—they tell us how it is

at a given moment. But they do not tell us how it came to be that way.

For that we need to look at things dynamically—we need to look at

causes that explain why matter has come to be formed in the way that it has.

Change consists in matter taking on (or losing) form. Efficient and final

causes are used to explain why change occurs.

This is easiest to see in the case of an artifact, like a statue or a table.

The table has come into existence because the carpenter put the form of the

table (which he had in his mind) into the wood of which the table is

composed.

The carpenter has done this for the purpose of creating something he can

write on or eat on. (Or, more likely, that he can sell to someone who wants

it for that purpose.) This is a teleological explanation of there

being a table.

This seems like a plausible doctrine about artifacts: they can be explained both statically (what they are, and what they’re made of) and dynamically (how they came to be, and what they are for).

Causes of natural objects

But what about natural objects? Aristotle (notoriously) held that

the four causes could be found in nature, as well. That is, that there is

a final cause of a tree, just as there is a final cause of a table.

Here he is commonly thought to have made a huge mistake. How can there be

final causes in nature, when final causes are purposes, what

a thing is for? In the case of an artifact, the final cause is the

end or goal that the artisan had in mind in making the thing.

But what is the final cause of a dog, or a horse, or an oak tree?

-

What they are used for? E.g., pets, pulling plows, serving as building materials,

etc. To suppose so would be to suppose Aristotle guilty of reading

human purposes and plans into nature. But this is not what he has

in mind. -

Perhaps he thinks of nature as being like art, except that the artisan is

God? God is the efficient cause of natural objects, and God’s purposes are

the final causes of the natural objects that he creates.

No. In both (a) and (b), the final cause is external to the object.

(Both the artisan and God are external to their artifacts; they impose form

on matter from the outside.) But the final causes of natural objects are

internal to those objects.

Final causes in nature

-

The final cause of a natural object—a plant or an animal—is

not a purpose, plan, or “intention.” Rather, it is whatever lies at

the end of the regular series of developmental changes that typical

specimens of a given species undergo.The final cause need not be a purpose that someone has in mind.

I.e., where is a biological kind: the of an

is what embryonic, immature, or developing s are all tending to grow

into. The of a developing tiger is to be a tiger. -

Aristotle opposes final causes in nature to chance or

randomness. So the fact that there is regularity in nature—as Aristotle

says, things in nature happen “always or for the most part”— suggests to him that biological individuals run true to form. So this end, which

developing individuals regularly achieve, is what they are “aiming at.”Thus, for a natural object, the final cause is typically identified

with the formal cause. The final cause of a developing plant or animal

is the form it will ultimately achieve, the form into which it grows

and develops.References: 198a25, 199a31, 415b10,

715a4ff. -

This helps to explain why form, mover, and often coincide (“the last three often amount to one,” as Aristotle says (198a25)). I.e., why one and the same thing can serve as three of the causes—formal, efficient, and final.

The of a (developing) tiger is just (to be) a tiger (i.e. to

be an animal with the characteristics specified in the definition of a tiger).

Thus, the final cause () and formal cause (essence) amount to the same thing.

And Aristotle also says that a source of natural change (efficient cause) is “a thing’s

form, or what it is, for that is its end and what it is for” (198b3). Hence,

one and the same thing serves as formal, final, and efficient cause.Claims like “a tiger is for the sake of a tiger” or “an apple tree is for

the sake of an apple tree” sound vacuous. But the identification of formal

with final causes is not vacuous. It is to say, about a developing entity,

that there is something internal to it which will have the result that

the outcome of the sequence of changes it is undergoing —if it runs

true to form —will be another entity of the same kind—a tiger,

or an apple tree. -

So form and coincide. What about the efficient cause?

The internal factor which accounts for this cub’s growing up to be a tiger

(a) has causal efficacy, and (b) was itself contributed by a tiger (i.e.

the cub’s father).This can be more easily grasped if we realize that for Aristotle questions

about causes in nature are raised about universals. Hence, the answers

to these questions will also be given in terms of universals. The questions

that ask for formal, final, and efficient causes, respectively, are:- What kind of thing do these flesh-and-bones constitute?

- What has this (seed, embryo, cub) all along been developing into?

- What produces a tiger?

The answer to all three questions is the same: “a tiger.” It is in this sense

that these three causes coincide. -

Aristotle’s account of animal reproduction makes use of just these points

(cf. I.21, II.9 and . Z.7-9):-

The basic idea (as in all change) is that matter takes on form. The form

is contributed by the male parent (which actually does have the form), the

matter by the female parent. This matter has the potentiality to be informed

by precisely that form. -

The embryonic substance has the form potentially, and can be “called by the

same name” as what produces it. (E.g., the embryonic tiger can be called

a , for that is what it is, potentially at least.) [But there

are exceptions: the embryonic mule cannot be called by the name of its male

parent, for that is a (1034b3).] -

The form does not come into existence. Rather, it must exist beforehand,

and get imposed on appropriate matter. In the case of the production of

artifacts, the pre-existing form may exist merely potentially. (E.g., the

artist has in mind the form he will impose on the clay. Nothing has

to have the form in actuality.) -

But in the case of natural generation, the pre-existing form must exist in

actuality: “there must exist beforehand another actual substance

which produces it, e.g. an animal must exist beforehand if an animal is produced”

(1034b17).

-

The basic idea (as in all change) is that matter takes on form. The form

-

So the final cause of a natural substance is its form. But what is the form

of such a substance like? Is form merely shape, as the word

suggests? No. For natural objects—living things—form is more complex.

It has to do with function.We can approach this point by beginning with the case of bodily organs. For

example, the final cause of an eye is its function, namely, sight.

That is what an eye is for.And this function, according to Aristotle, is part of the formal cause

of the thing, as well. Its function tells us what it is. What it is

to be an eye is to be an organ of sight.To say what a bodily organ is is to say what it does—what

function it performs. And the function will be one which serves the purpose

of preserving the organism or enabling it to survive and flourish in its

environment.Since typical, non-defective, specimens of a biological species do survive

and flourish, Aristotle takes it that the function of a kind of animal is

to do what animals of that kind typically do, and as a result of doing

which they survive, flourish, and reproduce. Cf. Charlton (, p. 102):. . . the widest or most general kind of thing which all non-defective members

of a class can do, which differentiates them from other members of the next

higher genus, is their function. -

To say that there are ends () in nature is not to

say that nature has a purpose. Aristotle is not seeking some one answer to

a question like “What is the purpose of nature?” Rather, he is seeking a

single kind of explanation of the characteristics and behavior of natural

objects. That is, plants and animals develop and reproduce in regular ways,

the processes involved (even where not consciously aimed at or deliberated

about) are all toward certain ends. -

There is much that can be said in opposition to such a view. But at least

it is not ridiculous, as is sometimes supposed. In so far as functional

explanation still figures in biology, there is a residue of Aristotelian

teleology in biology. And it has yet to be shown that biology can get along

without teleological notions. The notions of function, and what something

is for, are still employed in describing at least some of nature.

Go to next lecture

on Substance, Matter, and Form.

Go to previous

lecture on Aristotle on Change

Return to the PHIL 320 Home Page

Copyright © 2006, S. Marc Cohen

[NEW] Lecture on 4 causes | if cause – NATAVIGUIDES

The Four Causes

What are there four of?

-

Aristotle’s doctrine of the four causes is crucial, but easily misunderstood.

It is natural for us (post-Humeans) to think of (what Aristotle calls) “causes”

in terms of our latter-day notion of cause-and-effect. This is misleading

in several ways:-

Only one of Aristotle’s causes (the “efficient” cause) sounds even remotely

like a Humean cause. -

Humean causes are events, and so are their effects, but Aristotle

doesn’t limit his causes in that way. Typically, it is substances

that have causes. And that sounds odd.

-

Only one of Aristotle’s causes (the “efficient” cause) sounds even remotely

-

But to charge Aristotle with having only a dim understanding of causality

is to accuse him of missing a target he wasn’t even aiming at. We must keep

this in mind whenever we use the word “cause” in connection with Aristotle’s

doctrine. -

We will begin with the question, What is it that Aristotle says there are four of? The Greek word is

(plural ); sometimes it takes a feminine form, (plural

). And what is an ? Part of Aristotle’s point is

that there is no one answer to this question.An is just whatever one can cite in answer to a “why?” question.

And what we give in answering a “why?” question is an explanation. So an

is best thought of as an explanation than as a cause. -

Even so, that’s not enough. First, Aristotle thinks that you can ask what the aitia of this table are, and it’s

not clear what sense, if any, it makes to ask for an explanation of the table. Second, he

thinks that, in some sense, a carpenter is an aition of a table, and it’s not clear in

what sense, if any, a carpenter (or anything like a carpenter) could be an explanation of

anything.Here perhaps Ackrill’s “explanatory factor” is a more illuminating translation of

aition. That is, an aition is something that plays a role as an explanatory

factor in the explanation of something. But, as we’ll see, there are many kinds of explanations.

Where to find the doctrine in Aristotle’s texts

-

In RAGP: . II.3; and (extensively) in . A.3

ff. See also . 639b12ff -

Additionally (not in RAGP): . II.11; . Δ.2;

335a28-336a12.

The traditional picture

The picture is Aristotle’s, but the names of the causes are not. Quotations from Physics II.3, 194b24 ff:

-

Material cause:

“that out of which a thing comes-to-be and which persists is said to be a cause, for example, the bronze is a cause of a statue, the silver is a cause of a bowl, and the genera of these [is also a cause].”

-

Formal cause:

“the form or paradigm, and this is the formula of the essence … and the parts that are in the formula.”

-

Efficient cause:

“the primary starting point from which change or rest originates; for example, someone who has given advice is a cause, the father [is a cause] of a child, and in general what does [is a cause] of what is done and what alters something [is a cause] of what is altered.” -

Final cause:

“[something may be called a cause] in the sense of an end (telos), namely, what something is for; for example, health [is a cause] of walking.”

This account makes it seem as if Aristotle is offering a catalog of causes, and is claiming that

each thing has four different kinds of cause. But what the account misses is the idea that there

is something ambiguous about the notion of aition.

The ambiguity of aition

Aristotle warns us of the ambiguity at 195a5: “causes are spoken of in many ways.” This is his usual formula for telling us that a term is being used ambiguously.

That is, when one says that

is the of , it isn’t clear what is meant until

one specifies what sense of is intended:

- is what is [made] out of.

- is what it is to be .

- is what produces .

- is what is for.

This makes it hard for us to get clear on what Aristotle was up to, since

neither “cause” nor “explanation” is ambiguous in the way Aristotle claims

is. There is no English translation of

that is ambiguous in the way (Aristotle claims) is. But if

we shift from the noun “cause” to the verb “makes” we may get somewhere.

The ambiguity of makes

Aristotle’s point may be put this way: if we ask “what makes something

so-and-so?” we can give four very different sorts of answer—each appropriate

to a different sense of “makes.” Consider the following sentences:

- The table is made of wood.

- Having four legs and a flat top makes this (count as) a table.

- A carpenter makes a table.

- Having a surface suitable for eating or writing makes this (work as) a table.

Aristotelian versions of (1) - (4):

1a. Wood is an of a table.

2a. Having four legs and a flat top is an of a table.

3a. A carpenter is an of a table.

4a. Having a surface suitable for eating or writing is an

of a table.

These sentences can be disambiguated by specifying the relevant sense of

in each case:

1b. Wood is what the table is made out of.

2b. Having four legs and a flat top is what it is to be a table.

3b. A carpenter is what produces a table.

4b. Eating on and writing on is what a table is for.

Static vs. Dynamic Causes

Matter and form are two of the four causes, or explanatory factors. They

are used to analyze the world statically—they tell us how it is

at a given moment. But they do not tell us how it came to be that way.

For that we need to look at things dynamically—we need to look at

causes that explain why matter has come to be formed in the way that it has.

Change consists in matter taking on (or losing) form. Efficient and final

causes are used to explain why change occurs.

This is easiest to see in the case of an artifact, like a statue or a table.

The table has come into existence because the carpenter put the form of the

table (which he had in his mind) into the wood of which the table is

composed.

The carpenter has done this for the purpose of creating something he can

write on or eat on. (Or, more likely, that he can sell to someone who wants

it for that purpose.) This is a teleological explanation of there

being a table.

This seems like a plausible doctrine about artifacts: they can be explained both statically (what they are, and what they’re made of) and dynamically (how they came to be, and what they are for).

Causes of natural objects

But what about natural objects? Aristotle (notoriously) held that

the four causes could be found in nature, as well. That is, that there is

a final cause of a tree, just as there is a final cause of a table.

Here he is commonly thought to have made a huge mistake. How can there be

final causes in nature, when final causes are purposes, what

a thing is for? In the case of an artifact, the final cause is the

end or goal that the artisan had in mind in making the thing.

But what is the final cause of a dog, or a horse, or an oak tree?

-

What they are used for? E.g., pets, pulling plows, serving as building materials,

etc. To suppose so would be to suppose Aristotle guilty of reading

human purposes and plans into nature. But this is not what he has

in mind. -

Perhaps he thinks of nature as being like art, except that the artisan is

God? God is the efficient cause of natural objects, and God’s purposes are

the final causes of the natural objects that he creates.

No. In both (a) and (b), the final cause is external to the object.

(Both the artisan and God are external to their artifacts; they impose form

on matter from the outside.) But the final causes of natural objects are

internal to those objects.

Final causes in nature

-

The final cause of a natural object—a plant or an animal—is

not a purpose, plan, or “intention.” Rather, it is whatever lies at

the end of the regular series of developmental changes that typical

specimens of a given species undergo.The final cause need not be a purpose that someone has in mind.

I.e., where is a biological kind: the of an

is what embryonic, immature, or developing s are all tending to grow

into. The of a developing tiger is to be a tiger. -

Aristotle opposes final causes in nature to chance or

randomness. So the fact that there is regularity in nature—as Aristotle

says, things in nature happen “always or for the most part”— suggests to him that biological individuals run true to form. So this end, which

developing individuals regularly achieve, is what they are “aiming at.”Thus, for a natural object, the final cause is typically identified

with the formal cause. The final cause of a developing plant or animal

is the form it will ultimately achieve, the form into which it grows

and develops.References: 198a25, 199a31, 415b10,

715a4ff. -

This helps to explain why form, mover, and often coincide (“the last three often amount to one,” as Aristotle says (198a25)). I.e., why one and the same thing can serve as three of the causes—formal, efficient, and final.

The of a (developing) tiger is just (to be) a tiger (i.e. to

be an animal with the characteristics specified in the definition of a tiger).

Thus, the final cause () and formal cause (essence) amount to the same thing.

And Aristotle also says that a source of natural change (efficient cause) is “a thing’s

form, or what it is, for that is its end and what it is for” (198b3). Hence,

one and the same thing serves as formal, final, and efficient cause.Claims like “a tiger is for the sake of a tiger” or “an apple tree is for

the sake of an apple tree” sound vacuous. But the identification of formal

with final causes is not vacuous. It is to say, about a developing entity,

that there is something internal to it which will have the result that

the outcome of the sequence of changes it is undergoing —if it runs

true to form —will be another entity of the same kind—a tiger,

or an apple tree. -

So form and coincide. What about the efficient cause?

The internal factor which accounts for this cub’s growing up to be a tiger

(a) has causal efficacy, and (b) was itself contributed by a tiger (i.e.

the cub’s father).This can be more easily grasped if we realize that for Aristotle questions

about causes in nature are raised about universals. Hence, the answers

to these questions will also be given in terms of universals. The questions

that ask for formal, final, and efficient causes, respectively, are:- What kind of thing do these flesh-and-bones constitute?

- What has this (seed, embryo, cub) all along been developing into?

- What produces a tiger?

The answer to all three questions is the same: “a tiger.” It is in this sense

that these three causes coincide. -

Aristotle’s account of animal reproduction makes use of just these points

(cf. I.21, II.9 and . Z.7-9):-

The basic idea (as in all change) is that matter takes on form. The form

is contributed by the male parent (which actually does have the form), the

matter by the female parent. This matter has the potentiality to be informed

by precisely that form. -

The embryonic substance has the form potentially, and can be “called by the

same name” as what produces it. (E.g., the embryonic tiger can be called

a , for that is what it is, potentially at least.) [But there

are exceptions: the embryonic mule cannot be called by the name of its male

parent, for that is a (1034b3).] -

The form does not come into existence. Rather, it must exist beforehand,

and get imposed on appropriate matter. In the case of the production of

artifacts, the pre-existing form may exist merely potentially. (E.g., the

artist has in mind the form he will impose on the clay. Nothing has

to have the form in actuality.) -

But in the case of natural generation, the pre-existing form must exist in

actuality: “there must exist beforehand another actual substance

which produces it, e.g. an animal must exist beforehand if an animal is produced”

(1034b17).

-

The basic idea (as in all change) is that matter takes on form. The form

-

So the final cause of a natural substance is its form. But what is the form

of such a substance like? Is form merely shape, as the word

suggests? No. For natural objects—living things—form is more complex.

It has to do with function.We can approach this point by beginning with the case of bodily organs. For

example, the final cause of an eye is its function, namely, sight.

That is what an eye is for.And this function, according to Aristotle, is part of the formal cause

of the thing, as well. Its function tells us what it is. What it is

to be an eye is to be an organ of sight.To say what a bodily organ is is to say what it does—what

function it performs. And the function will be one which serves the purpose

of preserving the organism or enabling it to survive and flourish in its

environment.Since typical, non-defective, specimens of a biological species do survive

and flourish, Aristotle takes it that the function of a kind of animal is

to do what animals of that kind typically do, and as a result of doing

which they survive, flourish, and reproduce. Cf. Charlton (, p. 102):. . . the widest or most general kind of thing which all non-defective members

of a class can do, which differentiates them from other members of the next

higher genus, is their function. -

To say that there are ends () in nature is not to

say that nature has a purpose. Aristotle is not seeking some one answer to

a question like “What is the purpose of nature?” Rather, he is seeking a

single kind of explanation of the characteristics and behavior of natural

objects. That is, plants and animals develop and reproduce in regular ways,

the processes involved (even where not consciously aimed at or deliberated

about) are all toward certain ends. -

There is much that can be said in opposition to such a view. But at least

it is not ridiculous, as is sometimes supposed. In so far as functional

explanation still figures in biology, there is a residue of Aristotelian

teleology in biology. And it has yet to be shown that biology can get along

without teleological notions. The notions of function, and what something

is for, are still employed in describing at least some of nature.

Go to next lecture

on Substance, Matter, and Form.

Go to previous

lecture on Aristotle on Change

Return to the PHIL 320 Home Page

Copyright © 2006, S. Marc Cohen

Poolz – Cause, if You Could [atmospheric chill downtempo]

Poolz Cause, if You Could 🧡

Download: https://poolzmusic.bandcamp.com/track/causeifyoucould

🎧 Spotify Playlist: http://bit.ly/AmbientSpotify

Ambient Chill Downtempo

📸 Instagram: http://bit.ly/AmbientInstagram

🎁 Ambient Shop: https://teespring.com/stores/ambient

💬 Originality is the art of concealing your source.

Franklin P. Jones

🧡 Poolz

https://soundcloud.com/poolz

https://www.facebook.com/PoolzOfficial

https://twitter.com/yorick1996

https://poolzmusic.bandcamp.com

https://open.spotify.com/artist/1IcZePw1Z3tQX2kQxNQjFl

https://www.youtube.com/user/PoolzOfficial

💿 Suggested track: https://youtu.be/lEMrzP_gbf0

📷 Picture by Joseph Ashraf

https://unsplash.com/photos/anHThKy94MU

✅ Check out our 24/7 livestream

https://youtube.com/c/AmbientMusicalGenre/live

🖤 Ambient Releases

https://ambientmusicalgenre.bandcamp.com

🎵 Submit your music:

https://www.submithub.com/blog/ambient

🕊️ Follow AmbientMusicalGenre

https://www.ambientmusicalgenre.net

https://soundcloud.com/ambientmusicalgenre

https://youtube.com/AmbientMusicalGenre

https://facebook.com/AmbientMusicalGenre

https://vk.com/ambientmusicalgenre

https://twitter.com/AmbiiMG

นอกจากการดูบทความนี้แล้ว คุณยังสามารถดูข้อมูลที่เป็นประโยชน์อื่นๆ อีกมากมายที่เราให้ไว้ที่นี่: ดูความรู้เพิ่มเติมที่นี่

![Poolz - Cause, if You Could [atmospheric chill downtempo]](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/XBAEcHAV9Gc/maxresdefault.jpg)

SLANDER – Love Is Gone ft. Dylan Matthew (Lyrics Terjemahan Indonesia) ‘I’m sorry, don’t leave me’

Hi

Lyrics video with Indonesia translation

Maaf ya jika ada salahsalah

Original song by SLANDER Love Is Gone ft. Dylan Matthew

background anime 🏞️ : the garden of worlds \\ kotonoha no niwa

I do not own any of these contents I uploaded except my own songs. If you want your track to get removed please contact me here

[email protected]

Thanks For Watching

imsorry tiktok sadsong

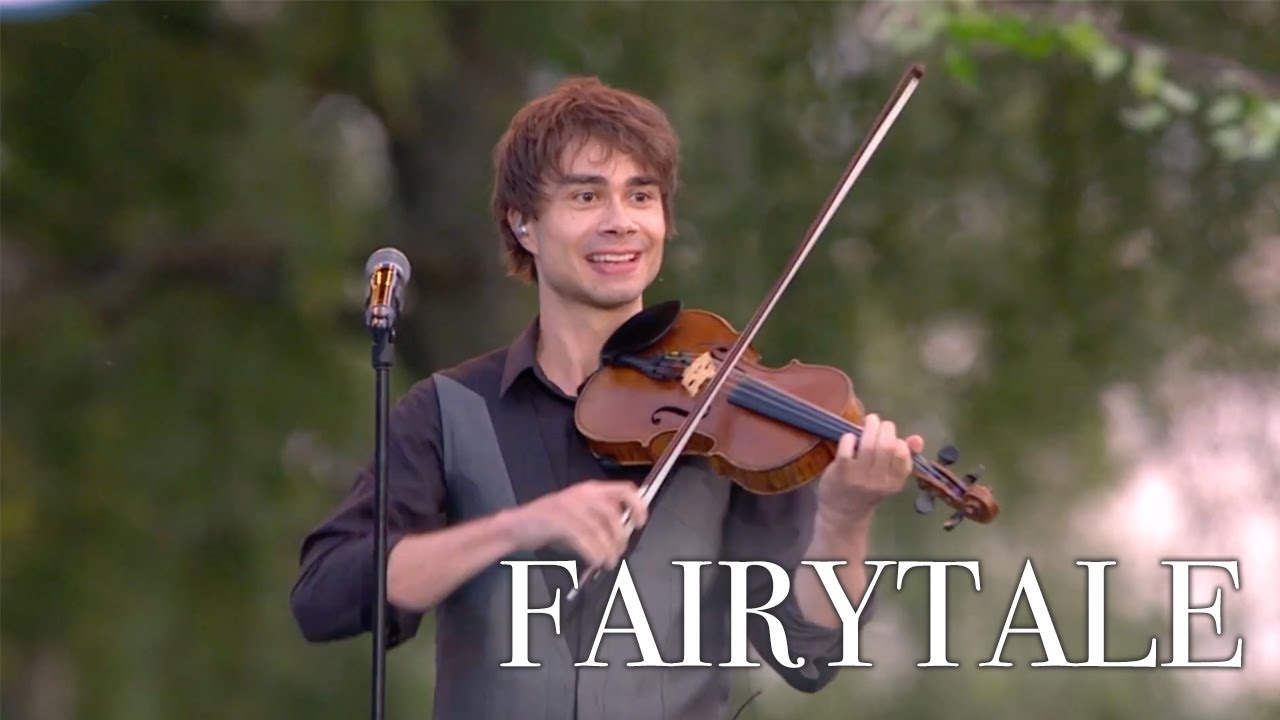

Fairytale – Alexander Rybak wins \”Best song in Eurovision History\”

All copyrights belong to TV2.no

In a public voting by TV2.no between 25 ESCsongs, \”Fairytale\” by Alexander Rybak, won the title as \”Best Eurovision Song of All times\”.

The winning song was announced in the TVbroadcast of \”Allsang på Grensen\” August 7th 2019.

More Information: http://www.alexanderrybak.com/2019/08/08/fairytalewonthetitleasthebestescsongofalltimesbyviewersvoting/

FOLLOW ALEXANDER

Instagram : http://instagram.com/rybakofficial

Web Site : http://www.alexanderrybak.com

Facebook : http://www.facebook.com/alexanderrybak

Twitter : https://twitter.com/AlexanderRybak

Vkontakte : http://vk.com/rybakofficial

CONTACT:

http://www.alexanderrybak.com/booking/

IF A CAUSE IS WORTH DYING FOR THEN BE OST Shin Evangelion 3.0+1.0 Thrice Upon a Time

Bonne écoute à tous

Will Linley – miss me (when you’re gone) [Official Audio]

Listen to miss me (when you’re gone) here: https://WillLinley.bio.to/MissMeID

Follow Will:

TikTok: https://www.tiktok.com/@williamlinleymusic?

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/willlinleyy/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/will_linley

Lyrics:

Uh oh, I don’t wanna think about

How my mind is slowly losing track of the time

And I start to trip on the chemicals

And you, light up another cigarette in the night

And I start to float and romanticize

All the things we do

When I met you in the summer we were falling in love

Thought it was a fling, but that wasn’t enough

Caught up in our feelings at the very first touch

And all I wanna say is

When I found you, I found me

Always gone through life in the backseat

If you walk out, I’ll crash now

Cause I’ve been thinking about it for too long

Lately I’ve been thinking about it all wrong

All I’m gonna do is miss me when you’re gone

Ohhh

I’ll miss me when you’re gone

I don’t know how to say it

But when I think about us, it tears my heart up to think about you walking away

I guess that all things come to an end

Ohhh

But it’s been a couple of weeks and that’s enough to believe

That you were gonna stick around instead of walking out on me

And now I’m lying here thinking about how

When I met you in the summer we were falling in love

Thought it was a fling, but that wasn’t enough

Caught up in our feelings at the very first touch

And all I wanna say is

When I found you, I found me

Always gone through life in the backseat

If you walk out, I’ll crash now

Cause I’ve been thinking about it for too long

Lately I’ve been thinking about it all wrong

All I’m gonna do is miss me when you’re gone

ohhh

I’ll miss me when you’re gone

When I found you, I found me

Always gone through life in the back seat

If you walk out I’ll crash now

Mmmh

When I found you, I found me

Always gone through life in the back seat

If you walk out I’llcrash now yeah

When I found you, I found me

Always gone through life in the backseat

If you walk out, I’ll crash now

Cause I’ve been thinking about it for too long

Lately I’ve been thinking about it all wrong

All I’m gonna do is miss me when you’re gone

Ohhh

I’ll miss me when you’re gone

WillLinley missmewhenyouregone Alternative

![Will Linley - miss me (when you're gone) [Official Audio]](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/dJzQbIYbJzM/maxresdefault.jpg)

นอกจากการดูบทความนี้แล้ว คุณยังสามารถดูข้อมูลที่เป็นประโยชน์อื่นๆ อีกมากมายที่เราให้ไว้ที่นี่: ดูวิธีอื่นๆLEARN FOREIGN LANGUAGE

ขอบคุณมากสำหรับการดูหัวข้อโพสต์ if cause